Land Use Designation and Zoning Codes—What’s the Difference?

To understand the difference between land use designation and zoning codes, begin with intent. If you’re not familiar with zoning codes it’ll help to start with an introduction to zoning codes.

The zoning code gives developers, landowners, and builders a set of specific rules for what can and can’t be developed on a property. This is accomplished with minimum lot sizes, height requirements, etc. Conversely, land use designations provide a certain “character” for a property—accomplished with a density restriction.

*This discussion will be limited to residential property types.

Land Use Designation Example

Property Profile

Address: 123 Fake Street, Fakeville, FA

Lot Size: 1 acre (43,560 sq. ft.)Zoning: R-1 5000

Zoning: R-1 5000

Land Use Designation: Single Family Residential Low Density

Notes

- Zoning code requires minimum lot size of 5000 sq. ft.

- Land use designation requires one to three dwelling units per acre (usually expressed as 1 to 3 du/ac)

Per the example, if you only consider your zoning, then you’ll be misled into thinking your yield is 8 units. After all, you’ve got 43,560 square feet to work with and only need to hit 5000 square feet per lot. (For now, we’re not worried about square footage for roads, utilities, open space, etc.) But the upper end of the land use designation restricts you to a maximum of 3 units to the acre.

For most, this is where the education on zoning and land use would end. But so far, we’ve only discussed how zoning and land use work on paper. For landowners and developers working with cities, it’s crucial to understand the difference between land use and zoning in the context of the entitlement process.

Which leads me to a big idea that many people miss: land use always trumps zoning.

Zoning changes are relatively easily—the keyword being relatively. When it is easy to get a zoning amendment or variance, it’s because the new zoning falls within the parameters of the existing land use designation (per the chart).

| Zoning (min. lot) | Proposed Zoning (min. lot) | Land Use (du/ac) | Chance for Approval? | |

| Scenario #1 | 12,000 sq. ft. | 4000 sq. ft. | 1 – 3 | No |

| Scenario #2 | 14,000 sq. ft. | 10,000 sq. ft. | 1 – 3 | Yes |

In scenario one, the proposed zoning—which would allow for a lot size of 4000 sq. ft.—makes no sense in the context of the land use designation. If the city wants a density of 1 to 3 units per acre, they intend for that area to be developed with houses with big backyards and lots of space. A 4000-sq. ft. lot is not consistent with that vision.

Scenario two, however, proposed a reduction in lot size that will still allow for large lots. Thus, you could argue that the character of the neighborhood wouldn’t be changed. Of course, there are no guarantees and you could easily be shot down. But you’re sure to be shot down in scenario one.

How Land Use Designations are Created

Changing land use designation is much harder than changing zoning. A land use change is accomplished with a general plan amendment. But before we get into general plan amendments, let’s back up a step to what a general plan is and how it relates to land use designation.

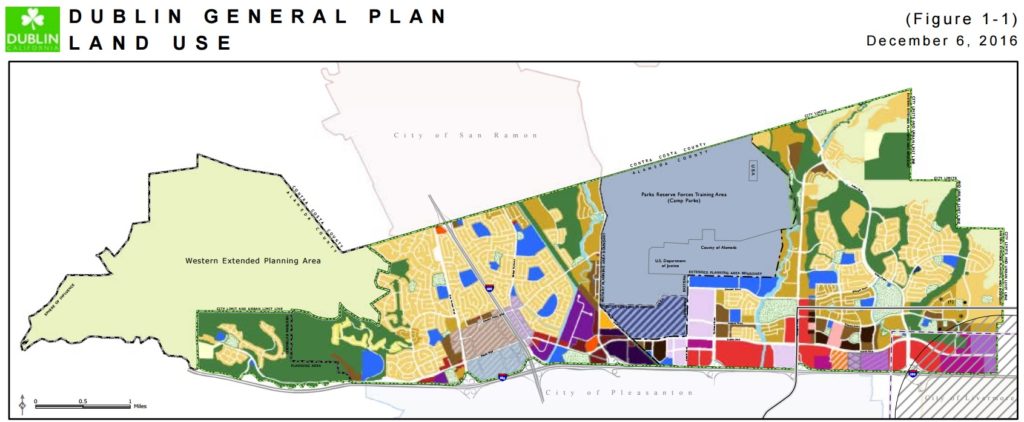

The city’s general plan is the document that creates land use designations. Keep in mind that different cities use different terms—land use designation/classification/code. A general plan is like the city’s constitution for development. California state law requires every city in the state to create one.

All general plans must contain at least seven elements: land use, circulation, housing, conservation, open space, noise, and safety.

As you may have guessed, land use is the element that contains the info on land use classifications.

To change the land use of a property, a city must evaluate that proposed change on the rest of the general plan elements. For example, the City of Banning’s guide on general plan amendments says, “Changes in a General Plan usually mean amended goals or objectives in the development policies of the City.”

With a general plan amendment, you’re trying to convince the city to align their goals with your goals.

What that means for a landowner trying to change their land use is that they must convince the city why the city’s goals should align with the landowner’s goals.

This is at the crux of why land use classifications are so much harder to change than zoning codes. Zoning codes exist to carry out the intent of the land use designation. So, if you want a zoning change but don’t need a new land use, your goals will still be in line with the city’s goals, theoretically.

If a general plan is like a city’s development constitution, zoning codes are the laws that support it. Like an unconstitutional law, zoning codes inconsistent with the general plan are struck down.

- 7 Endangered Species that Hurt Land Values [Bay Area]

- 5 Ways the Expiration of Tentative Maps Gets Extended

- Tentative Map Automatic Time Extensions Explained

- Tentative Tract Map Calculator FAQ

- CEQA Exemptions—An Introduction for Land Owners

- The CEQA Checklist—An Introduction for Landowners

- The CEQA Process–An Introduction for Landowners

- Land Use Designation and Zoning Codes—What's the Difference?

- An Introduction to Zoning Codes [Example]

- Four Factors that Attract Land Buyers

- 5 Questions Landowners Should Ask their Agent

- What's a Tentative Map and Why Does it Matter?

- How Comps Skew Residential Land Value Expectations

- Trump Takes Step back on Affordable Housing

- Developer and Builder: Who does what?