What’s a Tentative Map and Why Does it Matter?

The approval of a tentative map, according to the BRE, “is a significant milestone in the development process, and is a point at which much uncertainty regarding the project has been removed.”

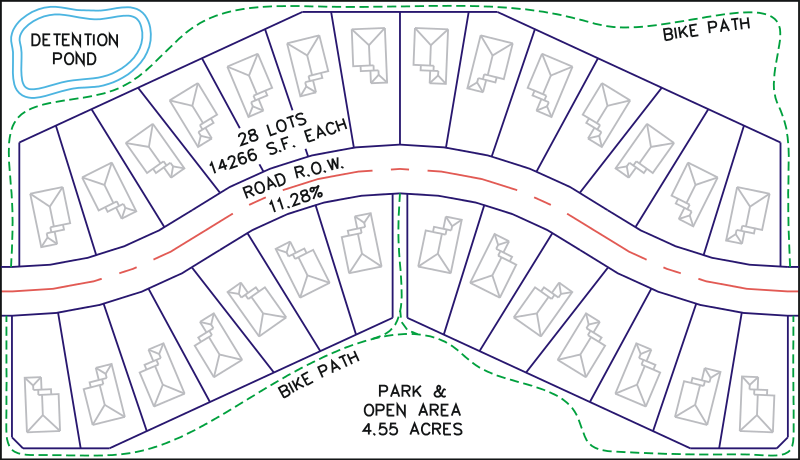

This may not sound like much, but the value of a 10-acre, raw parcel of land could easily increase tenfold with a well-crafted, approved tentative map. This value increase is mostly because an approved tentative map is much less risky to buy than a raw piece of land. That’s assuming the project is also designed well.

For this reason, much of the work a developer does is centered around obtaining tentative map approval.

The California BRE estimates the time to take land from raw and unentitled to an approved tentative map to be a minimum of two years and a maximum of over ten years. (Figure 7, page 34)

There are costs, in addition to the time, research, and manpower it takes to process a tentative map. Developers must hire professional consultants because only a Licensed Land Surveyor or registered Civil Engineer may prepare a tentative map. But this is just one of the many consultants a developer needs to hire to create a salable project. And assembling this professional team costs a lot of money.

Various cities can and do, by local ordinance, condition approvals on soils investigations which require the expertise of geotechnical engineers and/or biologists. Developers need architects to draw up detailed floor plans and building elevations, which will also be subject to city review. Smart developers also hire a marketing consultant to help determine the best home and lot design for the project from a marketing perspective.

Also, every tentative map is subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). CEQA requires an initial study be done to evaluate the environmental impacts of development. The result of this study is either a Negative Declaration (ND), Mitigated Negative Declaration (MND), or further study in the form of an Environmental Impact Report (EIR). In the event of an ND or an MND, a filing fee of a couple thousand will be required.

If an EIR is deemed appropriate the developer will be on the hook for several thousand dollars and the project will be delayed by a year or more.

Once all the soils testing is done, plans are drawn up, city officials and neighbors are met with, revisions are made, filing and review fees are paid, the tentative map application will be deemed complete. Then a public hearing will be held. The public hearing is always political, and often contentious.

A negative public response can sway local officials who were previously supportive, which adds another layer of risk to the process.

The requirements for tentative map approval detailed above are the minimum. Special circumstances such as wetlands or land in flood areas may require additional review by other government entities.

Despite the arduous process of drafting a tentative map, the time and money invested are not what makes a tentative map so important; it is the removal of risk. The tentative map is the last ‘discretionary’ approval required. Discretionary means that the city is granted police power, under the Map Act, to deny the map if they believe it will, “place the residents of the subdivision or the immediate community, or both, in a condition dangerous to their health and safety.”

This means that, even with the proper zoning, general plan designation, and a tentative map professionally prepared with all fees paid, a development can be denied at the discretion of the local entity.

The tentative map process, which may take many years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, may end in denial at the discretion of a few elected officials.

This is why development is such risky business, and why developers often make a fortune or lose it all.

- 7 Endangered Species that Hurt Land Values [Bay Area]

- 5 Ways the Expiration of Tentative Maps Gets Extended

- Tentative Map Automatic Time Extensions Explained

- Tentative Tract Map Calculator FAQ

- CEQA Exemptions—An Introduction for Land Owners

- The CEQA Checklist—An Introduction for Landowners

- The CEQA Process–An Introduction for Landowners

- Land Use Designation and Zoning Codes—What's the Difference?

- An Introduction to Zoning Codes [Example]

- Four Factors that Attract Land Buyers

- 5 Questions Landowners Should Ask their Agent

- What's a Tentative Map and Why Does it Matter?

- How Comps Skew Residential Land Value Expectations

- Trump Takes Step back on Affordable Housing

- Developer and Builder: Who does what?