The CEQA Process–An Introduction for Landowners

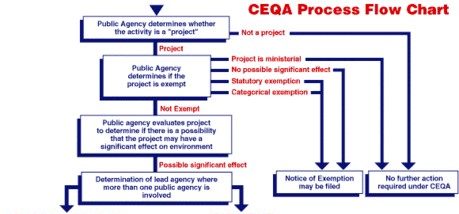

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) regulates the environmental impacts of residential projects. In California, the CEQA process regulates all physical development.

CEQA applies to anything deemed a “project.” And a project is any activity with the “potential for a direct physical change or a reasonably foreseeable indirect physical change in the environment.” (Per the California Natural Resources Agency).

This post will outline the CEQA process in the context of a private residential development of seven or more new units.

Otherwise, we run the risk of being bogged down in the mountain of CEQA technicalities. You can follow this discussion visually with the CEQA flow chart provided to us by the CA government.

CEQA Process: Project/No Project

The first question CEQA asks is whether the proposed activity is a project. The full definition of a project, which I referenced above goes as follows:

“a private activity which must receive some discretionary approval … from a government agency, which may cause either a direct physical change in the environment or a reasonably foreseeable indirect change in the environment.”

Note that the emphasis I added refers to the two things that make an activity a project.

A discretionary approval requires judgment. For example, a city approves or disapproves a tentative map depending on if it conforms to the character of the existing neighborhood. What I decide is conforming and what you decide is conforming may be different. So that would be a discretionary approval.

The other type of approval is ministerial. An example of a ministerial approval is an agency’s approval of road improvements. So long as the roads meet the agency’s specifications, the agency must approve the road.

If you’re familiar with tentative maps, you know that a tentative map’s approval is discretionary. And new construction is a direct physical change. Thus, per CEQA’s definition of a project, every residential development is considered a project under CEQA.

Exemptions

There are several types of exemptions for projects. There are also several exceptions to those exemptions. (That’s right, exceptions to exemptions.) The California Natural Resources site has more on statutory exemptions and categorical exemptions.

For now, we’re going to skip projects that may qualify for exemptions. For residential development, generally they apply to infill projects when a property has already been developed. Thus, the potential for new or worse environmental effects is reduced. But again, there are exceptions.

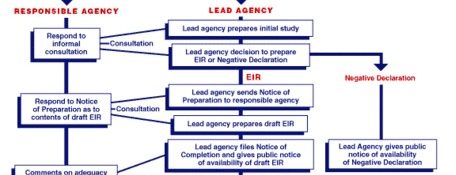

CEQA Process: Initial Study

Once the public agency deems that a project may have a significant effect, the fun begins. It starts with an initial study. These are reports that evaluate a project’s effects on 18 environmental factors.

The initial study determines whether an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) or a Negative Declaration (ND) is required. (More on what those are later.)

This determination is based on whether the project may have a “significant impact.” CEQA guidelines establish thresholds of significance which outline what a significant impact is. Individual cities are encouraged to establish their own thresholds. In practice, however, most cities use Appendix G of the CEQA guidelines.

Environmental Impact Report (EIR)

For many developers, the determination on whether an EIR or MND is needed is the difference between financial success and failure.

EIR’s must contain detailed discussions of potential environmental effects, methods to reduce or avoid the effects, and project alternatives. They often run up to 300 pages for complex projects. Here’s an example of an EIR for a project in San Francisco which fills almost 200 pages.

These documents require expensive professional consultants and hours of review by city staff. The total cost will run into the several thousands. The filing fee alone costs developers and builders around $3000. But the cost is not usually what kills projects. It’s the time delay. According to real estate attorney Nav Atwhal, the EIR process takes between 18 and 24 months. Often the process extends for more than two years.

This makes it difficult for developers to find investors, because they’re forced to wait for a long process to unfold. And once that process does unfold, the investors risk losing everything depending on the decision. That’s why a developer’s track record is so important. Investors are betting money on a developer’s ability to navigate a risky, complex process.

Negative Declarations or Mitigated Negative Declarations

An MND must include:

- A brief description of the project

- A proposed finding saying the project has a less than significant environmental effect

- A copy of the Initial Study

- Mitigation measures

Of course, you’ll still need to pay for hours of review and professional consultants. But these documents aren’t nearly as extensive as an EIR. The bulk of the work is already done in the Initial Study.

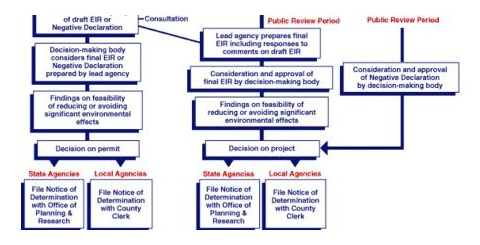

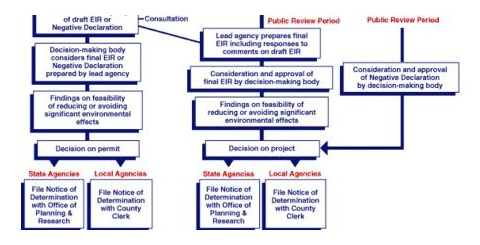

CEQA Process: Public Review

Whether CEQA requires an MND or an EIR, there will be an extensive public review process.

Until this point, the project has faced hurdles which required extensive technical expertise.

In public review, everyone gets a voice, from environmental and labor groups to your next-door neighbor. Developers must address their concerns or risk controversy and potential litigation.

This is where developers must employ a great deal of finesse. The length of the CEQA and entitlement processes are obstacles enough in themselves. Unaddressed concerns can lead to controversy at best and litigation at worst. Either one slows down the process, costing the developer valuable time and money.

Decision

The lead agency decides on the project. The lead agency is usually the planning commission or city council. Their decision is recorded with a notice of determination. Developers are not off the hook yet, though. They must wait out the final appeal period before moving forward. The end of the appeal period signifies the end of the formal CEQA process.

- 7 Endangered Species that Hurt Land Values [Bay Area]

- 5 Ways the Expiration of Tentative Maps Gets Extended

- Tentative Map Automatic Time Extensions Explained

- Tentative Tract Map Calculator FAQ

- CEQA Exemptions—An Introduction for Land Owners

- The CEQA Checklist—An Introduction for Landowners

- The CEQA Process–An Introduction for Landowners

- Land Use Designation and Zoning Codes—What's the Difference?

- An Introduction to Zoning Codes [Example]

- Four Factors that Attract Land Buyers

- 5 Questions Landowners Should Ask their Agent

- What's a Tentative Map and Why Does it Matter?

- How Comps Skew Residential Land Value Expectations

- Trump Takes Step back on Affordable Housing

- Developer and Builder: Who does what?